“Gong Gong!”

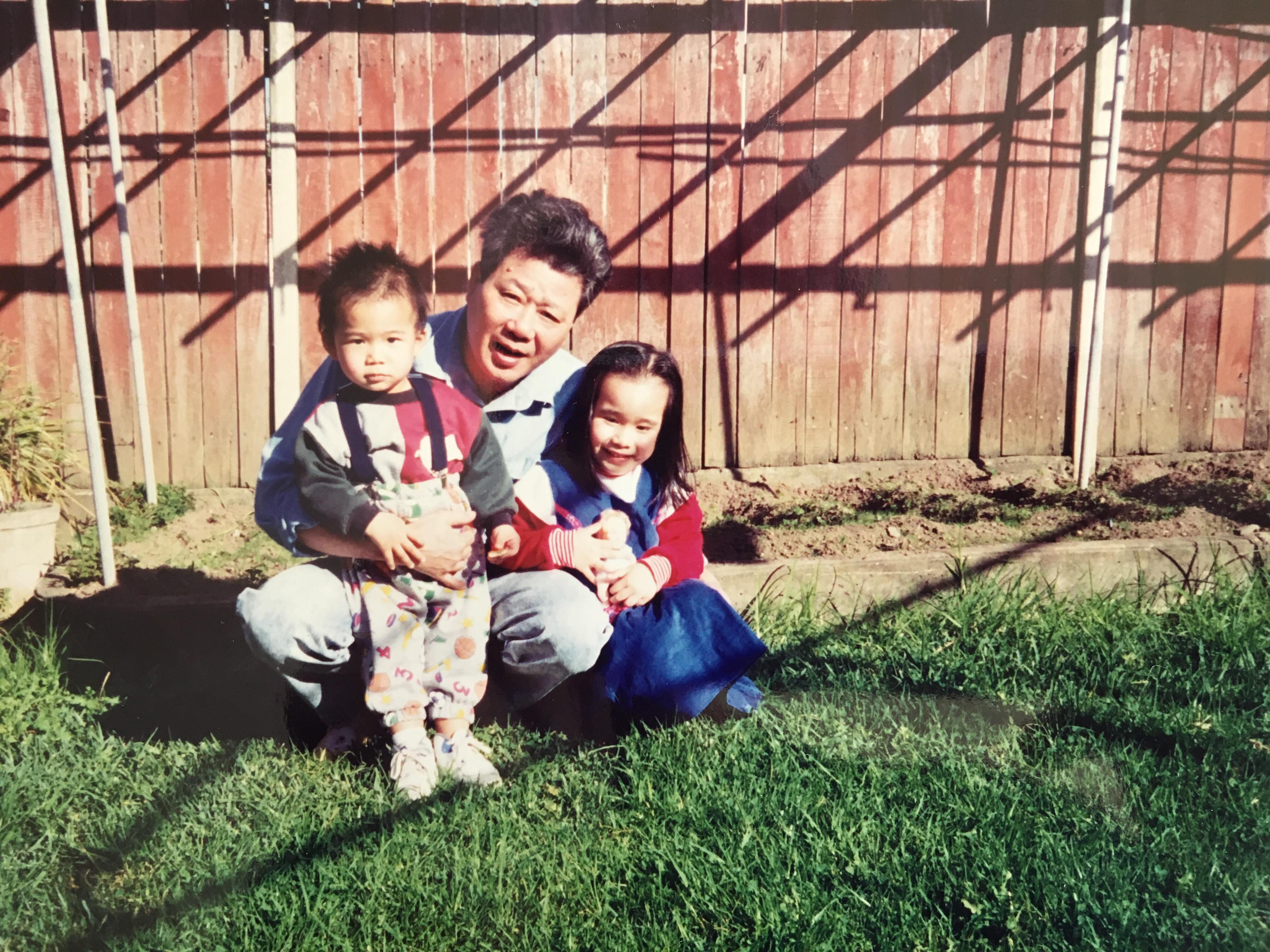

I raced towards my beaming grandfather who was on his way home after an afternoon at the local TAB. I threw out my arms for a big hug, but he laughingly dodged my open arms, grabbed the back of my neck and ruffled my hair instead. He has never been the hugging type and after thirty years I haven’t stopped trying.

My Gong Gong looked the same as always. The same beret, the same jeans, the same sneakers and the same puffy jacket that he wears every winter. For the past four years I have tried to visit Sydney every July to celebrate his birthday. This year he turns 84, and while he’s still quite healthy, there’s no denying that his movements are slower and his speech more slurred.

“Did you win anything today Gong Gong?”

“I lost a dollar today but yesterday I won two dollars!” he replied, slowly but proudly.

“Good job Gong Gong!” I replied, amused by his simple and joyful spirit.

If there was anything I have learned from growing up in a migrant home, it’s the value of being content with little and the freedom that a simple life promises in a complicated world. My Gong Gong was born in China into an educated upper-class family that sold herbal medicine for a living. He enjoyed a comfortable life up until the Cultural Revolution which saw millions of Chinese persecuted. After my Gong Gong witnessed the unexplained murder of his father, he quickly made plans to escape into Hong Kong.

My Gong Gong joined a movement of ‘Freedom Swimmers’ who made their escape from China by swimming into Hong Kong. The route was dangerous and often fatal but for the persecuted, Hong Kong was a promise of freedom, food and a future. My Gong Gong dived into freedom with two friends but along the way, one was eaten by a shark and another shot dead by Chinese authorities. Weary and starving, he arrived on the shores of freedom as the lone survivor.

I heard this story for the first time around the dinner table in my childhood home in Sydney. It’s a remarkable story about courage being born out of adversity and yet always told with a sense of denial and detachment. How else are you meant to cope with such horrors; the uprooting of your home, the unexplained murder of your father, the death of your friends and the shame of leaving two younger sisters behind?

I had always thought that my Gong Gong had made his first migration decision in the 1970’s when he arrived in Australia in search for work. It broke my heart to learn that he had been running for much longer. Whether in Hong Kong or Australia, my Gong Gong was always humble and willing to bear the burdens of hard and cheap labour. Unlike me, he wasn’t born into a context where freedom and peace could be demanded. He had to fight to secure it for himself, his wife, his children and grandchildren. Perhaps this is why a $2 win at the local TAB and peaceful stroll back home is a reason for celebration.

My Gong Gong lit a cigarette and we began our walk back to my childhood home. Being a fast ‘Sydney’ walker, I’m usually spotted powering my short legs at an aggressive speed but that afternoon I intentionally slowed down to match my Gong Gong’s pace, soaking in every precious second of being able to walk ‘home’ together again. As we shuffled down the main road, I felt a sense of protectiveness. Once upon a time, it was he who had to slow down for me.

My Gong Gong spent many years raising a family of five as a chef and kitchen-hand in Chinese restaurants across Sydney. Without any formal qualifications or a handle of English, he was loyal to any kitchen who would hire him. His retirement routine now consists of a morning walk around the neighbourhood, planting vegetables in his garden, watching Hong Kong dramas and visiting the TAB with his diminishing circle of friends. On special days, his children and grandchildren will come home for a meal around the table. Visiting my grandparents now involves an interstate flight and a 90-minute train ride. Some people would call it a waste of time, but for me it is always a nostalgic adventure down memory lane.

We arrived at the familiar pink gate and I ushered my Gong Gong inside, excited to welcome the familiar scent of incense from the family shrine and the soothing sound of hot oil hitting the family wok.

“I’M HOME!” I cried out at the top of my lungs.

Just as I expected, my Por Por popped out from the kitchen with a huge smile and lunged at me with one of her comforting cuddles. In a hurried and ever-changing world, I’ve come to appreciate peace in predictability. No matter how much time passes, I know that stepping into my grandparent’s home is the closest thing I will ever get to time travel. The same lace curtains, the same mismatched wall-art, the same clock, and the same kitchenware that they have used for decades. Unlike the world around me, my grandparents have never seen the need to upgrade their standard of living. Over the years, my many gifts have ended up in their display cabinets, after all, why replace something that works just fine?

After a brief hug, my Por Por raced back to the kitchen where she continued frantically frying short ribs on the wok. I took a seat at the kitchen bench, admiring her work and allowing my senses to be delighted by the flavours of my childhood. My eye suddenly noticed a shiny modern appliance which stood out like a sore thumb in such a vintage space.

“You got a new toaster!?” I asked my grandmother with genuine shock.

I loved her old toaster. It was a trustworthy and sturdy appliance built in the 80’s – nothing like the appliances today which break down every couple of years. As I quietly mourned yesterday’s toaster, my Gong Gong retrieved a plate of prawns from the fridge in order to add the final touches to his signature dish. The prawns had been skilfully butterflied and I watched with delight as my Gong Gong smothered them with crushed garlic.

“Yuuuum!! Steamed garlic prawns!!” I hollered with giddy excitement. I’ve learned over the years to make a big deal about my grandparent’s cooking.

“Your Gong Gong spent the whole morning cutting prawns and picking out the dirty intestine! Do you realise how much work goes into making your favourite dishes? It takes hours to make and then you eat it all up in two seconds!” my Por Por cried out teasingly.

“Thanks Gong Gong!” I responded, embarrassed by their generosity. It suddenly dawned on me that I had turned up empty handed with not even a bag of fruit!

Unlike my loud and boisterous Por Por who proceeded to tease me at the top of her lungs, my Gong Gong prepared his dish in silence. I watched him intently because I knew that he was communicating volumes through his cooking, which in our family is a labour of love. He has never said to me “I love you” or “I miss you” or “I’m proud of you” and yet every dish he generously serves is a cue for unconditional love and acceptance – even if I have nothing to bring to the table.

To this day, my grandparents have no idea what I do for work. They don’t ask questions about my job, my salary or my job title. They have never shamed me with unrealistic expectations or measured my worth by my achievements or my looks. They have never made me feel like a burden to their busy lives or that I owe them for raising me. I know that their love for me is unconditional because their generosity towards me has always come from a place of lack with no strings attached.

As working-class migrants, I know that my grandparents aren’t particularly impressive by our society’s standards. Their outward appearance is far from stylish, their achievements will never make the headlines, and they could never defend or speak up for themselves because of their limited language skills. But what they have taught me from a place of lack has shaped the best parts of who I am. Through their humble example, I have learned that human value is not derived by personal performance, contentment is the anchor for joy, and that you don’t need to own a lot in order to give a lot.

As I savoured the first bite of my Gong Gong’s garlic prawns, I reminded myself that with or without life’s trophies, all people are worthy of love, acceptance and a place at the table.